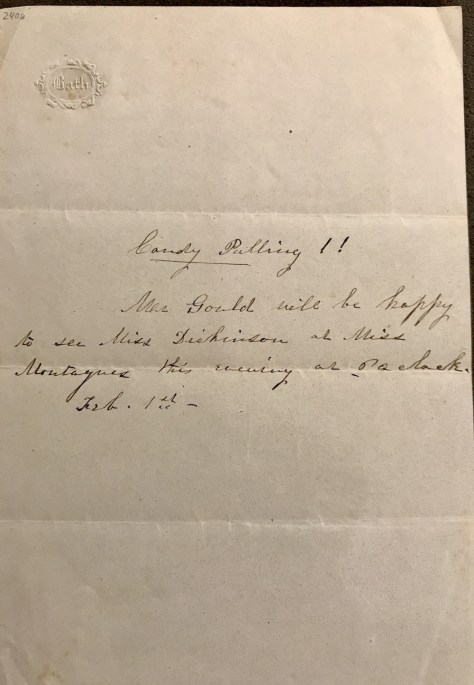

This post is the third in a series about my experiences at the NEH summer program, Emily Dickinson: Person, Poetry, and Place. If you haven’t read the first two, you can find them here and here. My experiences on the third day may differ slightly from those of other participants as we divided into groups.

Next, we a heard a lecture from Dickinson scholar Christanne Miller from the University at Buffalo. As I mentioned in my previous post, there have been three major editions of Dickinson’s poems since the 1950’s. Thomas H. Johnson’s was the first to make an attempt to date the poems chronologically and restore some of Dickinson’s intentions. Ralph W. Franklin’s Variorum edition has been widely influential in Dickinson scholarship. Christanne Miller has a new edition called Emily Dickinson’s Poems: As She Preserved Them. The organization of Miller’s book differs from Johnson’s and Franklin’s precisely as the subtitle describes. The first section of Miller’s book includes Dickinson’s fascicles; the second, Dickinson’s poems saved on unbound sheets joined together with a fastener (Dickinson may or may not have fastened the manuscripts); the third, loose manuscripts in Dickinson’s possession; the fourth, others’ transcriptions of her poems with no extant manuscripts; the fifth, poems given away to others. The concept is really interesting, and I really wish I had brought my copy of this book for Christanne Miller to sign. I considered packing it and decided not to in order to save space. I hope I run into her again so I might get it signed. It’s a beautiful book with images of manuscripts.

Miller’s lecture was on “Editing Dickinson.” From everything I’ve learned in this workshop, editing Dickinson is difficult because of all the variants in her manuscripts, but we also have a large body of well-preserved work, and we can’t say that of every poet. One big takeaway from Miller’s lecture is that there is always more than one way to edit an author, and editors make decisions largely based on the tastes of the eras in which they are working. She said that no edition is neutral; each edition is a lens into the times in which it was created. As such, while our modern audience might see Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson as heavy-handed editors, changing slant rhymes and word choices, a case can be made that they knew their audience well and were editing the poems to suit their audience. Dickinson was ahead of her time. I can’t remember if Miller said it or if someone else did, but someone remarked that Amy Lowell believed Dickinson to be a “precursor of the Imagists.” In any case, Todd and Higginson’s editions of the poems were wildly popular, and we have much for which to thank them.

Miller also argues that Dickinson may not have distinguished much between poetry and letters. Most tantalizing for me as a teacher was the fact that there is evidence Dickinson was instructed to select alternative word choices in her school compositions. I love to think of Emily Dickinson’s writing instruction in school. Another issue that Miller acknowledged is that Dickinson made many typographical errors, often over and over. For instance, I had noticed she almost always uses the contraction “it’s” when she clearly means the possessive “its.” In the manuscripts, the mistake is clear, and it’s not a word choice variant. Franklin retains these typographical and spelling errors in his edition of her poems. While Miller points out that spelling and punctuation were not rigidly fixed or standard in Dickinson’s time, I have always found the kinds of errors she makes interesting. Most interesting regarding punctuation was Miller’s comment about the ubiquitous dashes in Dickinson’s poetry. While Dickinson does use a lot of dashes, some of them may be commas and periods. If you examine the manuscripts, it is hard to tell whether or not the marks are dashes. We all do such things when we are writing, especially in our drafts. Here is an example of a manuscript I saw in which it’s hard to tell if we’re seeing dashes or something else.

One last comment about Miller’s lecture and I’ll move on (we’re already at nearly 700 words!). Miller believes that Dickinson composed at least the beginnings of her poems largely in her head. The last stanzas often include more variant word choices (not that the beginning stanzas never do, but you see a lot in the last stanzas). Also, the last stanzas are sometimes the most problematic. I know as a reader, I have more difficulty understanding the last stanzas of her poems. Also important for teachers: Dickinson tries out a number of speakers and perspectives. We are usually so good about asking students to think of the speaker as separate from the poet, but I think we might be guilty of forgetting to do that with Dickinson’s poetry. One way to help students with her poetry is to ask them to read it aloud and to look for natural “sentences.” Don’t worry about the dashes and enjambment.

Next, my group joined Martha Ackmann for a discussion of Dickinson’s poetry. She is delightful—funny, knowledgeable. She quoted Dickinson’s letters and poetry frequently, and without consulting notes. Ackmann suggests that we can look at many of Dickinson’s poems as Dickinson’s philosophy of poetry—ars poetica. We did a close reading of “I reckon—When I count at all—” (Franklin 533). Ackmann reminded us as teachers to slow down when we are reading and teaching Dickinson. She also reminded us that Dickinson’s schooling largely consisted of declaiming lessons and memorizing, and she had an encyclopedic knowledge of many texts, including the Bible. When Dickinson is ambiguous, she intends to be. Ackmann also said we must acknowledge the “primacy” of Dickinson’s imagination. We tend not to give her credit for being able to imagine experiences she never had or places she never went. My favorite quote from our discussion was Ackmann’s argument that “She lived in her own mind, and what a place to live.” Ackmann also argues that Dickinson didn’t care about publication, but she did want her poems to live on. She wanted to do more than publish; she wanted to be immortal, a subject discussed in many of her poems.

After lunch, we took a self-guided landscape tour, which is something you can do yourself if you visit the Emily Dickinson Museum. You can even use your cell phone and either call into a number to follow the tour or use the QR code provided. They also have wands you can use to listen to the tour if you don’t have a cell phone or don’t want to use one. The tour was narrated mostly by poet Richard Wilbur. After the tour, we met with our curriculum groups to discuss how the essential questions and key understandings for our lessons or units were shaping up.

We ended the day with a reading from Martha Ackmann, “Mary Lyon, Emily Dickinson, and Women’s Education.” Mary Lyon founded the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, where Dickinson went to school at the age of 16. Ackmann is writing a book tentatively titled Vesuvius at Home about ten monumental days in Dickinson’s life. Ackmann is a narrative nonfiction writer, which means her books are all factual but use the techniques of storytelling. She fictionalizes nothing. She described how she writes each chapter, and the amount of work she puts in is incredible. She mentions enjoying Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, especially praising the way he begins the book, but she dislikes the fact that he invented dialog. She will not read narrative nonfiction that doesn’t have footnotes. Her book should be out in 2018, and I will be getting it for sure after the chapter I heard, which was about Emily Dickinson’s decision to continue to question her religious beliefs. You can see this questioning over and over in the poems. Ackmann is a Senior Lecturer in Gender Studies at Mount Holyoke College, the institution that grew out of Mary Lyon’s school. I understand the Emily Dickinson Museum has plans to host an author event when Ackmann’s book is published, so keep your eyes on the news, and I will see you there.