The third chapter of An Ethic of Excellence is a meaty one. After you’ve tackled school culture (chapter 2), this chapter asks you to think about the work.

The third chapter of An Ethic of Excellence is a meaty one. After you’ve tackled school culture (chapter 2), this chapter asks you to think about the work.

Don’t focus on students’ self-esteem before expecting them to do good work. The praise is not genuine, and students know it. Instead, encourage them to produce quality work, and the self-esteem will follow.

So, how do you inspire students to do excellent work?

The chapter is long, and I’ll do my best to digest.

Powerful Projects

Assignments should be authentic. “There’s only so much care and creativity that a student can put into filling in the blanks on a commercially produced worksheet” (65). In addition, assignments have to be connected to the learning. You are probably thinking that’s obvious, but there are a fair amount of projects assigned—and I’ve been guilty of it, too—that have nothing to do with what the students are studying. Berger gives the example of the science fair. After seeing my daughter through that particular drudge this year, I think he has a point: she picked a random science-related topic, went home and learned about it, and produced a project based on it. It didn’t have any connection to the science she was learning in school. He also describes making a diorama based on Pecos Bill and receiving an A for the project, despite not having read the book. There is a big difference between projects and project-based learning. He describes the classroom as “the hub of creation, the project workshop” (70). Projects are not something done outside of school. They are important work, done in class, with rubrics (often written in collaboration with students) and models. It strikes me that the flipped classroom model is a gift of more time to be able to spend on workshop in the classroom. Project components are broken down, with checklists and deadlines. The process might look the same for each project, but the projects themselves are not the same.

Building Literacy Through the Work

Use these projects to teach all the critical skills. Projects are not “an extra activity after the real curriculum and instruction is done” (72). Teach reading comprehension, analysis, understanding, writing skills, etc. through the process of creating the project.

Genuine Research

I love the example Berger gives of science experiments in school: “We called them experiments, but we didn’t really experiment. These were scientific procedures, prescribed by a book, that we were instructed to follow so that we could achieve a prescribed result, a result that our teacher knew ahead of time” (75). It seems like every experiment I ever did in school was just like the ones Berger describes. I often wondered what the point was. People already knew this information, so why were we wasting our time marching through a process? What did I really learn from doing these experiments? Well, one thing I learned is not to like science. And then I started making my own soap recently, and all of a sudden, chemistry was interesting to me. Not just interesting—fascinating. Even if you’ve made lots of soap, it can still surprise you and do things you didn’t expect it to do. That’s fun science. I can follow a procedure, but the results are not a given. I am actually learning a lot, and I only wish science had been this interesting to me in school. I never really had a chance to be a scientist in school. But Berger makes a good point when he says that “[t]eaching how to do original research doesn’t come easily to many teachers” (78). The key? Teachers need to “let go of their expectation that they need to be the expert in everything, the person who knows all the answers” (78).

The Power of the Arts

The arts are often cut in schools, but the arts are a powerful tool to enrich student work. Berger says, “The question for me is not whether we can afford to keep arts in our schools but how we can ensure that students put artistic care into everything that they do” (80).

Models

Berger is emphatic that the best way to help students understand what quality work looks like is to show them quality work. Rubrics and descriptions are not enough. While I agree wholeheartedly, the problem is that I don’t always have a student-created model. I can and have created models myself, but my work is not as powerful as a student’s work. Berger suggests borrowing one, but this isn’t always feasible either. I know there have been many times I’ve done a project that is different enough that I can’t find a model. Providing models is ideal, but it’s not always possible. However, Berger is right that the pride students take in being models for others is profound. I have seen it myself: students will ask years later if I still have x project. Berger doesn’t come right out and say so explicitly, but what I infer from this chapter is that you just cannot teach in a vacuum. You don’t have models? Someone else might. You need help figuring out something about an assessment? Someone else can help. This type of connection was the vision I had for the UbD Educators wiki.

Multiple Drafts

Berger describes the ways in which school is one of the last places where rough draft work is still acceptable. Teachers will chalk it up to not having enough time, etc., but ultimately, if you want polished work, that means students need to do multiple drafts. We have some work to do in school to establish multiple drafts as the norm instead of the signal that you failed to do it correctly the first time.

Critique

Berger describes a really interesting model for peer critiques in his classroom, and I think this part of the chapter offers really sound advice for how to move students towards more thoughtful critique. Critiques are boiled down to three rules: 1) Be Kind, 2) Be Specific, and 3) Be Helpful. Within these rules, students are protected from being hurt and are able to get real, helpful feedback. In addition to these three rules, Berger suggests the following guidelines (rules are never abandoned, but guidelines might be):

- “[B]egin with the author/designer explaining her ideas and goals, and explaining what particular aspects of the work she is seeking help with” (94). I think at first, you might need to put some sort of metacognitive reflection in place until students become acclimated to asking themselves these types of questions about their work.

- “[C]ritique the work, not the person.”

- Begin the critique with “something positive about the work, and then move on to constructive criticism” (94). This part can be hard, and it is easy to move into the danger zone of offering empty compliments. But it does help not to feel attacked right at the start. Teachers often call this the “sandwich.”

- “[U]se I statements when possible: ‘I’m confused by this,’ rather than ‘This makes no sense'” (94).

- “[U]se a question format when possible: ‘I’m curious why you chose to begin with this…?’ or ‘Have you considered including…?'” (94).

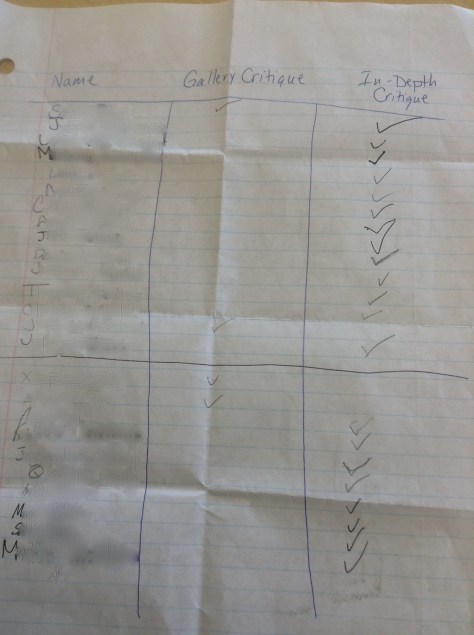

This advice strikes me as something that will be easy to implement in a classroom with a few small changes and some scaffolding upfront, but that will reap large dividends in terms of students’ thinking and understanding. Berger goes on to describe two main kinds of formal critique: 1) gallery critique, in which each student’s work is displayed and students “look at all the work silently before giving comments” (94), after which students discuss examples from the gallery that particularly impress them; 2) in-depth critique, which involves spending a substantial period of time critiquing a single student or group’s work as a class. Berger also adds that when you are talking about written work, it’s important to “differentiate between critiquing for specific content qualities and critiquing for mechanics (conventions); if this isn’t clear, critique can quickly become just copyediting” (95). If you’ve ever tried peer editing and had it flop (I’m raising my hand here), it may be because students have the idea that critiquing is just proofreading.

Making Work Public

A lot of teachers do not make student work public for a variety of reasons, but a public audience does make the work more authentic and meaningful. As Berger points out, if work is public, “There is a reason to do the work well, and it’s not just because the teacher wants it that way” (99). Emphasis his. We should be offering our students opportunities to publish their writing and projects. I have a colleague that has difficulty with this idea because students do make errors. So don’t we all. I am continually finding small proofreading errors in work I have published here. I even found an apostrophe error in Berger’s book. Does it detract from his ideas? No. Students should be correcting their work and polishing it as much as possible, but we have to acknowledge when we talk about publishing student work that it won’t be perfect. We should not let that paralyze us and prevent us from doing it. Learning is messy. I don’t have the answer. One suggestion is not to assess the work until the students have corrected all the errors you have pointed out in your feedback. However, there is a reason, I think, that Berger mentions multiple drafts and critique before he mentions making the work public. That work of drafting and editing comes first.

Using Assessment to Build Stronger Students

Berger makes the statement that “U.S. students are the most tested in the world.” I have a hunch that this statement is true, but I would be interested to see if that statement can be verified through statistics. He goes on to say, “Oddly, test-taking skills have little connection to real life. When a student finishes schooling, she is judged for the rest of her life on the kind of person she is and the kind of work that she does. Rarely does this include how she performs on a test” (101-102). See, this is the problem most of us teachers have with testing. I gave one test in my English class last year—the final exam. I was supported in this. I very rarely give tests. They are not the best measure of student learning in my class, for sure. The only kinds of tests I can think of that we might take in “real life,” aside from driving tests and the like, are professional entrance exams like the Bar Exam. I am sure many professions have them. But how is the professional assessed after that? By the quality of his/her work, right? That is what we do in our society, yet it is not the kind of assessment advocated by those who dictate educators’ practices (many of whom are not educators themselves). Why? Because it’s easier than doing a real, authentic assessment. It is much harder to evaluate authentic assessment. Sometimes there is not a neat little letter grade you can put on it. It reminds me of this quote from Dead Poets Society after Mr. Keating has just had the class read the introduction to their text, the subject of which is how to evaluate poetry: “Excrement! That’s what I think of Mr. J. Evans Pritchard! We’re not laying pipe! We’re talking about poetry. How can you describe poetry like American Bandstand? ‘I like Byron, I give him a 42 but I can’t dance to it!'” Berger says, “If tests are the primary measure of quality, the majority of schools feel compelled to have students spend much of their time memorizing facts and preparing for tests” (102).

Berger imagines a different model for school:

Imagine if students were judged instead on the quality of student work, thinking, and character. Imagine an expectation that an adult should be able to enter a school and expect that any child in that school older than seven or eight would be ready to greet him politely, give an articulate tour of a well-maintained, courteous school environment, and present his portfolio of academic accomplishments clearly and insightfully, and that the student’s portfolio would contain original, high-quality work and document appropriate skill levels. If schools assumed they were to [sic] going to be assessed by the quality of student behavior and work evident in the hallways and classrooms—rather than on test scores—the enormous energy poured into test preparation would be directed instead toward improving student work, understanding, and behavior. Instead of working to build clever test-takers, schools would feel compelled to spend time building thoughtful students and good citizens. (102)

Berger also brings up the fact that grades are not the best motivators:

The strategy most often employed to create pressure for high standards is assigning grades to work. Ideally the promise of good grades and the threat of bad ones will keep everyone working hard. In reality, it doesn’t always work this way. (103)

Any first-year teacher can probably tell you about students who are not motivated by grades. Berger teaches in a school that has done away with grades. Some day I plan to write a huge treatise on grades and assessment because I have a lot of thoughts, but I need to do a lot of research. Suffice it to say that I do not see any reason why grades have to be the way we assess. However, Berger does give good advice if you do have to use grades: “Make sure the grades are seen by students as something they earn, rather than as the arbitrary decision of a teacher” (105).

Berger closes the chapter with discussion of a water study his students did, which was an authentic research assignment that had real-world implications for community members. It’s a perfect example of the kind of science I wish I had had more opportunity to do in school.

Like this:

Like Loading...

I have been writing this blog post in my head for months now, and I’m not sure I will really capture what I’m thinking.

I have been writing this blog post in my head for months now, and I’m not sure I will really capture what I’m thinking.