This post is the second in a series about my experiences at the NEH workshop Emily Dickinson: Person, Poetry, and Place last week. If you haven’t read the first post, you can access it here.

The second day of this workshop was one of my favorite days. We opened, as usual, with some time to write and reflect on an Emily Dickinson poem—Franklin 729, “The Props assist the House.”

The Props assist the House

Until the House is built

And then the Props withdraw

And adequate, erect,

The House supports itself

And cease to recollect

The Augur and the Carpenter—

Just such a retrospect

Hath the perfected Life—

A Past of Plank and Nail

And slowness—then the scaffolds drop

Affirming it a Soul—

We were invited to think about the poem through the lens of teaching, and I liked the prompt so much that I plan to use it in a department meeting early in the school year.

Next, we divided into smaller groups, and though the sequence of events differed depending on the assigned group, all workshop participants had the opportunity to engage in the following experiences in some order.

My group first went to Amherst College’s Frost Library to hear a lecture from Marta Werner, an Emily Dickinson scholar—”‘She does not know a route’: Reading Emily Dickinson’s Manuscripts.” Werner invited us to think of the manuscripts Emily Dickinson left behind almost like maps, where we can see a topography and travel from one continent to another, and even from one world to another. Werner noted that she believed Dickinson’s handwriting became more ungendered over time. Her earliest manuscripts are written in what Werner describes as a more feminine hand. There is certainly a lot to think about, but regardless of whether or not one agrees with this assessment (I can actually see it, having looked at some manuscripts both in person and online), I found it fascinating to learn that her handwriting changed so much over the course of her life that it is often through her handwriting that her manuscripts are dated.

I feel I should stop and explain something you might not know anything about if you haven’t engaged in a study of Dickinson’s poetry. I mentioned in my post yesterday that the first real attempt to date Dickinson’s poetry and arrange it chronologically as well as restore, as much as anyone can, Dickinson’s intentions free from the heavy editorial hands of Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, was a publication of her complete poems in the 1950’s by Thomas H. Johnson. There have been two more recent publications—Ralph W. Franklin’s Variorum Edition of the poems in three volumes, which is an attempt to show all the extant manuscripts, including variants, and also variant word choices Dickinson considered on single manuscripts. There is a reader’s edition of this same work, which was our main text for the workshop, and therefore why I refer to her poems by their Franklin numbers. Franklin set out to date the poems as accurately as possible and differs from Johnson somewhat. I mentioned there have been two more recent comprehensive editions of Dickinson’s poetry since Johnson’s, but I will save discussion of the second for a future post, as later in the week I had an opportunity to study Dickinson’s poetry with the editor of that third collection.

Dickinson left behind a variety of manuscripts in many stages of development. Some were mere scraps with ideas.

In the above example, it seems clear Dickinson was playing with the phrase that would later be used in Franklin 1286 “There is no Frigate like a Book.”

Dickinson also has drafts that seem to be in a clearly unfinished state. She has fair copies and also gift copies sent to friends and family. Just because a manuscript is copied out in a fair copy or gift copy, however, does not mean that it was a final draft. Dickinson often continued to change words and lines even after making fair copies and gift copies. In addition, there are also intermediate copies that Werner describes as “worksheet manuscripts” that show the continued consideration Dickinson was giving to a poem. Some of you may know that Dickinson bound some of her poems together in what Mabel Loomis Todd first described as “fascicles.” These were manuscripts sewn together with a needle and thread. Again, just because the poems were bound in fascicles does not mean Dickinson considered them final drafts. Dickinson was comfortable with a great deal more ambiguity and a lot less fixity than most of us. As such, we can’t really talk about her intentions with any sort of authority in some cases. We spent the remainder of our time with Werner discussing some poem variants. If you really want to go down a rabbit hole, looking at Emily Dickinson’s drafts is both interesting and maddening. You can examine many of her manuscripts online.

After Werner’s lecture, my group headed downstairs to the Frost Library’s archives. This was a real treat. We were able to examine several artifacts connected with Emily Dickinson, including the famous daguerreotype that is the only definitively authenticated picture of Emily Dickinson. It was very hard to photograph in the lighting.

We also were able to see a lock of Emily Dickinson’s hair. The color may surprise you.

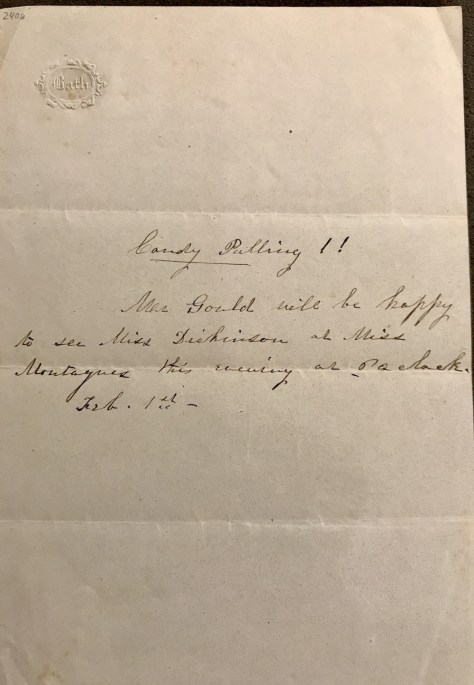

In addition, there were also some daguerreotypes of Emily Dickinson’s brother Austin and George Gould, who may have been an early suitor of Dickinson’s and sent her this invitation to a candy pulling.

On the back of this invitation, some 25 years after receiving the invitation, Dickinson wrote the poem “I suppose the time will come” (Franklin 1389). She saved the invitation all that time, and it’s tantalizing to think she was inspired by it when she wrote the poem and to wonder what she was thinking. Was she regretful about not taking him up on it? Or was she just making use of a scrap of paper she saved out of a sense of Yankee frugality?

We saw so many manuscripts that I will not share them all here, but I will share one last one that you will recognize.

I promise I’m not trying to be cute by sharing a slanted photo of the poem. There was a bad glare from the lights, as you can see, and I was attempting to take a picture in a way that would not cast a shadow on it and also reduce the glare. As you may have already surmised, we were not allowed to touch any of the artifacts. I don’t know if you can see it well enough in this image, but she actually wrote this poem on graph paper. Who has a sense of humor?

After lunch, we returned to the Emily Dickinson homestead for an object workshop. My small group headed over to the Evergreens, the home of Emily Dickinson’s brother Austin and his wife Susan Gilbert Dickinson. Nan Wolverton of the American Antiquarian Society (here in Worcester!) allowed us to examine two objects. I partnered with my friend Whitney, and we were given a small hearth broom and wastepaper basket to examine. We learned that the objects were both made by Native Americans. The broom was probably bought from a Native American peddler who traveled door-to-door selling wares, and Dickinson describes such events in her writing. The wastepaper basket was of a Penobscot design and probably bought as a souvenir when the family vacationed in Maine. It’s weird to think that people have always bought such things when they travel as mementos.

My group had some time to reflect, which Whitney and I used as a much-needed coffee break. At 4:00 PM we returned to Amherst College for a tour of the Beneski Museum. I have to admit I was wondering why we were doing this, but our guide, who is the museum’s educator, Fred Venne, made some intriguing connections between Dickinson’s poetry and the museum’s focal collection of dinosaur footprints. Venne is extremely funny and a great explainer. I learned that Dickinson might have studied with Edward Hitchcock, an early president of Amherst College and geologist who discovered the many examples of dinosaur tracks in Western Massachusetts. Though plate tectonics had not yet been discovered, Hitchcock apparently realized the Holyoke Range was formed through some kind of volcanic mechanism (because of the kinds of rocks he found, I imagine). In fact, had Pangaea not separated to form the coast at Boston, it might have split close to Amherst, and the coastline would look a lot different. In any case, the Holyoke Range was formed, and Emily Dickinson wrote this poem that seems wildly ahead of its time scientifically (Franklin 1691):

Volcanoes be in Sicily

And South America

I judge from my Geography

Volcano nearer here

A Lava step at any time

Am I inclined to climb

A Crater I may contemplate

Vesuvius at Home

I asked Fred Venne how on earth she could have known the Holyoke Range was formed through plate tectonics and vulcanism—it seemed like such advanced science for the time, and he told me it was because Edward Hitchcock was so advanced. He was the first to surmise that the footprints he was finding, the dinosaur tracks, were left behind by a large bird. It would be a very long time before paleontologists began thinking of dinosaurs as early birds. It was absolutely fascinating, and if you can visit the Beneski and talk to Fred Venne, you should. In the meantime, you can check out the museum’s new website. If you go to Special Features and look under “Voices,” you’ll see Emily Dickinson referenced.

I will write more about the rest of the workshop in future posts, but I hope at this point I’ve convinced you of a few things: 1) write to your representatives and senators about preserving the NEH; 2) if this workshop can continue because the NEH continues, please apply to be a part of it; it’s amazing, and 3) Emily Dickinson is a bottomless well, and one could devote a lifetime to scholarship of Dickinson and her world and always learn new things.