Of the subjects I proposed in my previous post, Writing Workshop received the most #1 votes. Google Docs rubrics received more votes if you count #2 and #3+ votes, but since I technically didn’t say to rank the choices, I’m going with Writing Workshop for this post and will write about Google Docs rubrics soon.

Of the subjects I proposed in my previous post, Writing Workshop received the most #1 votes. Google Docs rubrics received more votes if you count #2 and #3+ votes, but since I technically didn’t say to rank the choices, I’m going with Writing Workshop for this post and will write about Google Docs rubrics soon.

First, I need to mention that what I am doing with Writing Workshop is new to me. If you poll your students and ask them what they have typically done for Writing Workshop in the past, if they have done it all, they usually say that they exchanged papers with a peer or a small group of people, and they gave each other feedback. Ron Berger says in An Ethic of Excellence that “[m]any teachers also pair off students and ask them to critique each other’s writing. I suggest teachers take critique to a whole new level” (92). Berger goes on to say that

Critique in most classroom settings has a singular audience and a limited impact: whether from a teacher or peer, it is for the edification of the author; the goal is to improve that particular piece. The formal critique in my classroom has a broader goal. I use whole-class critique sessions as a primary context for sharing knowledge and skills with the group. (92)

I decided to try Berger’s idea after watching him work with elementary school students in this video:

I also showed this video to my students. Their reaction was interesting. Even after watching the drafting process, they insisted Austin traced the last butterfly. The improvement was too drastic. I pointed out that we watched the process in action, but they responded that the butterfly was better than anything they could draw, and they are in high school. But I reminded them that Austin went back to the drawing board several times. However, my point was made. Improvements do occur with multiple drafts, and specific feedback really can improve work. Of course, it was not lost on my students either that if elementary school students can give specific, targeted feedback that will help a peer improve his/her work, then so can they.

My students were ready to try it in my class. I found my volunteers to be the first students to have their work critiqued in what Berger calls an “in-depth critique” (94). I did not have trouble finding volunteers, as I feared I might. Here is Berger’s description of an in-depth critique:

When doing an In-Depth Critique, we look at the work of a single student or group and spend a good deal of time critiquing it thoroughly. Advantages to this style include opportunities for teaching the vocabulary and concepts of the discipline from which the work emerges, for teaching what comprises good work in that discipline, and opportunities for modeling the detailed process of making the work stronger. (94)

In-depth critiques are time-consuming. It took us an entire class period to do an in-depth critique on one paper. I suspect that we will get faster as the year goes on.

What we did first was have the writer share his/her vision for the paper and explain what he/she was hoping to achieve. Then the writer asked the class to focus on certain areas. One writer asked that his peers help him determine whether or not his paragraphs developed his thesis, for example.

Then, I asked the volunteer writers if they wanted to read their papers, or if they wanted me to do so. Both volunteers opted to have me read their papers, but I think it’s good to give students that option.

We read the paper through once, and I asked the students for general feedback about what they liked. For instance, one writer had done additional research and found a statistic from outside the short story we were analyzing (John Updike’s “A&P”) to develop one of his points. The class really liked that. So I asked them if they had thought of doing that, too, and none of them had. Boom. I just taught them it is OK to do additional research in order to make a point, and I also showed the students how this evidence was properly cited and that an entry for the source appeared on the Works Cited page.

Then we went through the paper nearly sentence by sentence and looked for how the entire piece of writing worked. Here is a short list of things I was able to discuss because they came up in the writing we examined:

- How to properly integrate quotes. Both writers had great examples of tightly integrated quotes and quotes that needed to be more tightly integrated.

- What to do when you have to change a quote slightly (use brackets).

- Using dependent clauses at the beginning of sentences and how to punctuate (and why it’s OK to start a sentence with ‘because.’ Teachers, really, you have to stop telling students not to do that).

- Using appositive phrases.

- Combining sentences.

- Stronger constructions. One student said “Quitting his job was not a good decision” or something similar, and I pointed out that phrasing the sentence this way was much more effective than “It was not a good decision for Sammy to quit his job.” We begin with a much stronger word, and we avoided that overused “it is,” “there was,” etc. that we see too often in student work.

- We had a live model of a peer’s work that had examples of good writing and writing in need of improvement. It’s helpful for students to see that writing doesn’t spill fully formed from the pen, and that all of us have areas of strength and weakness in our writing.

- Where it might be OK to cut redundant information, and where it might be necessary to clarify a point.

- How to pick an engaging title and why you should.

- Works Cited and in-text citations.

- Identifying areas where arguments are weak and need more development.

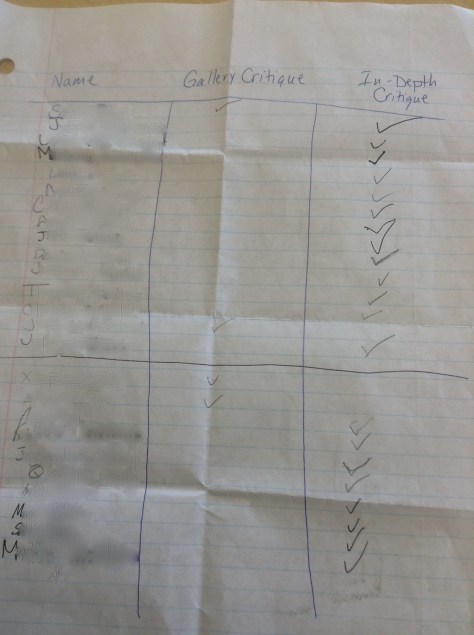

All of this and more just from looking at one paper. Yes, it was time consuming, but I can tell the students learned more about writing effectively, even if they didn’t necessarily take in every detail, than they would have if I had simply commented on their papers and handed them back. Workshop was way more effective than any time I have tried to go over such issues in class or in feedback given back to students. Perhaps the most telling feedback I received was when I passed around this paper and asked students to check whether they’d prefer an in-depth critique or gallery critique (passing papers around, reading silently, and commenting on the papers in general once we’re done). Here is how my students responded (names redacted; click on the image to see a larger version):

As you can see, the students overwhelmingly endorsed the value of this endeavor. I just have to figure out how we are going to read all of these papers!

As you can see, the students overwhelmingly endorsed the value of this endeavor. I just have to figure out how we are going to read all of these papers!

I can think of a couple of reasons, aside from time, that teachers might be reluctant to do this kind of Writing Workshop.

- But what can they do on their own?

- What about a timed writing situation?

I would argue that students don’t know how to do this on their own, but once they see the process modeled, they learn how. Obviously we don’t have time to do this with every essay. I’m wondering myself how we have time to do it with one essay. But you really don’t need to do it with each essay. Even picking a few volunteers to workshop can really help the others see the same patterns and issues in their own papers, and they can revise and edit after seeing it done. Another point to consider is why we ask students to do this kind of writing on their own when as adults, they can certainly get feedback on anything they write. Even published novelists have editors. Some of them even write with other people! Why do we tell students they have to go it completely alone, no help with revision or it’s not really their work?

The second argument is even more problematic because aside from standardized tests and exams, when in life do you really have to do timed writing? Deadlines, sure, but timed writing? I suppose I hold the radical notion that it doesn’t have much of a place in teaching writing because its antithetical to helping students see writing as a process and discourages students from doing the kind of revision and editing we want them to do. And then we complain when they turn in first-draft work on a final draft.

Aside from the overwhelming interest my students showed in workshopping their own papers, another interesting thing to note from this experiment is that one of my writers participated as fully in the revision as did his peers. He had his Google Doc open as we discussed the writing, and he made the edits he liked right there in class. He also suggested edits himself. If we ran into a sentence that needed work, he chimed it with, “Maybe instead I could say…” It was fantastic! It is the kind of metacognitive process we want to instill in our students.

I will try to share some further thoughts regarding logistics in a future post. Meanwhile, please feel free to share your thoughts in the comments.